Inge F. Hendriks

Until 1700 Russia had no native doctors

During its early history the majority of Russians had little or no access to qualified medical care, but relied on traditional folk and herbal remedies. In cities and at the courts of princes and boyars (noblemen) worked secular Russian and foreign folk healers called lechtsy (лечцы). They used traditional medicine and passed their medical knowledge and secrets from generation to generation. Widespread use was made of herbal remedies derived from plants such as sage, nettle, plantain or wild rosemary, and from animals, e.g. honey and cod liver oil. Tsar Mikhail Fyodorovich (1613-1645), the first reigning Romanov, instituted improvements in social welfare and healthcare. Around 1620 he established the Aptekarskiy Prikaz (Ministry of Pharmacy) in Moscow.(Fig. 1) In Russia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries pharmacists had the primary responsibility in healthcare. Medicine became more complicated. It changed from external application of herbs to herbal and drug prescriptions in combination with surgical treatments.

Peter the Great

After 1717

Oil on canvas

In public domain

Peter the Great radically reformed Medicine and medical education

Peter the Great (1672-1725) became Tsar of Russia at the young age of ten years, together with his handicapped half-brother Ivan Alekseevich (1682-1696); his half-sister Sophia acted as regent. (Fig. 2) This dual rule lasted until 1696, when Ivan Alekseevich died.

As a child Peter the Great had many friends in the slobodova, the foreigner’s area, in Moscow. One of his closest friends was the family’s court physician, Johan (Ivan) Termont, a skilled Dutch barber-surgeon.(Fig. 3) He not only taught him Dutch language, but was his first teacher on theoretical and practical medicine. After the death of his brother Ivan, Peter made his first visit to Europe with the Grand Embassy (a diplomatic mission to strengthen Russia’s alliance with a number of European countries) during1697-1698, which he again repeated in 1716-1717. His childhood friends and his travels abroad influenced Peters vision for the modernization of Russia. He introduced several innovations, including appointing doctors medicinae as decision makers in the healthcare system. This was continued by his successors.

Illustration for the play The Dutch Doctor

by Carlo Goldoni

Italy

Collected drawings of Venetian artists V

Paper, pen, brush, brown tint, ink. 9 × 11.2 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Received in 1925, originally ex coll. Yusupov

Inv. № ОР-20370

PHOTO: © THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM, ST PETERSBURG, 2019

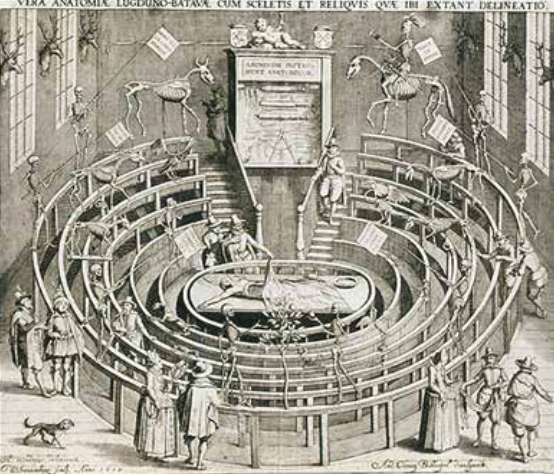

The window to Europe

In the seventeenth century the centre of anatomical studies moved from Italy particularly to the Netherlands (Holland), because Papal edict excluded all non-Catholics at Italian universities as a consequence of the Reformation. The Leiden university, founded in 1575 by Stadtholder Willem the Silent, was open to all students irrespective of race, nationality or religion and became famous for its anatomical and medical school.(Fig. 4) In October 1698 Tsar Peter the Great visited by carriage Leiden university and the anatomical theatre.(Fig. 5) Peter was very interested in the establishment and laws of this university. Govert Bidloo, professor of anatomy and medicine and besides Rector Magnificus of the university, presented him with a Latin general description of everything concerning the university. Bidloo was also the personal court physician of William III, Dutch Stadtholder and King of England. In 1691 William III appointed Govert Bidloo as superintendent of all civil and military doctors, pharmacists, surgeons, and hospitals in the Netherlands and England. Peter became befriended with the Stadtholder and visited him in the Netherlands as well as in England. Peter the Great sought another court-physician and Govert Bidloo recommended his nephew Nicolaas as court-physician, who graduated and defended his thesis at the Leiden university in 1696. Among his teachers were Carolus Drelincourt (1633-1697), who was also a tutor of his uncle and Herman Boerhaave. The father of Nicolaas was Lambert Bidloo a pharmacist in Amsterdam and brother of Govert.

The Tsar invited Nicolaas Lambertus Bidloo (1673/4-1735),(Fig. 6) who accepted Peter’s invitation in 1702 and became physician in ordinary to his Imperial Majesty in 1703. Before moving to Russia he held a successful medical practice in Amsterdam.

As his personal physician Bidloo accompanied the Tsar on his campaigns and travels within Russia and on his trips to Europe. Peter was, however, a healthy individual so Bidloo had little to occupy him in a professional capacity and after some time became dissatisfied with his function and asked the Tsar to be relieved of his duties as his personal physician “… due to my indisposition and weakness”, although from his workload in subsequent years there was little evidence of “indisposition and weakness”. Peter agreed to his request and commanded him by a decree of 1706 to build a hospital near the German settlement on the banks of the Yauza river in Moscow with a school to teach students anatomy and surgery. Bidloo was not only a renowned physician but also a talented architect and he himself drew up the plans for the hospital, medical school, a botanical garden and an anatomical theatre, where the Tsar regularly attended dissections.(Fig. 7)

The medical hospital school was officially opened on November 21, 1707 by Peter the Great himself.

The curriculum at the hospital school included anatomy conducted on corpses in the anatomical theatre, surgery, internal medicine, autopsy, chemistry, drawing and Latin. Pharmacy was studied in the Botanical Garden. The hospital complex was the first for modern education in Russia.

Bidloo became the director of the hospital, professor of anatomy and surgery at the school and manager of the anatomical theatre until his death on 23 March 1735. After the death of Nicolaas Bidloo, Antonius de Theyls, a Russian of Dutch origin, who studied at Leiden university, became his successor. Over a period of almost 70 years the school trained many barber-surgeons for the army and navy and prepared talented graduates for a PhD degree abroad especially for Leiden University.

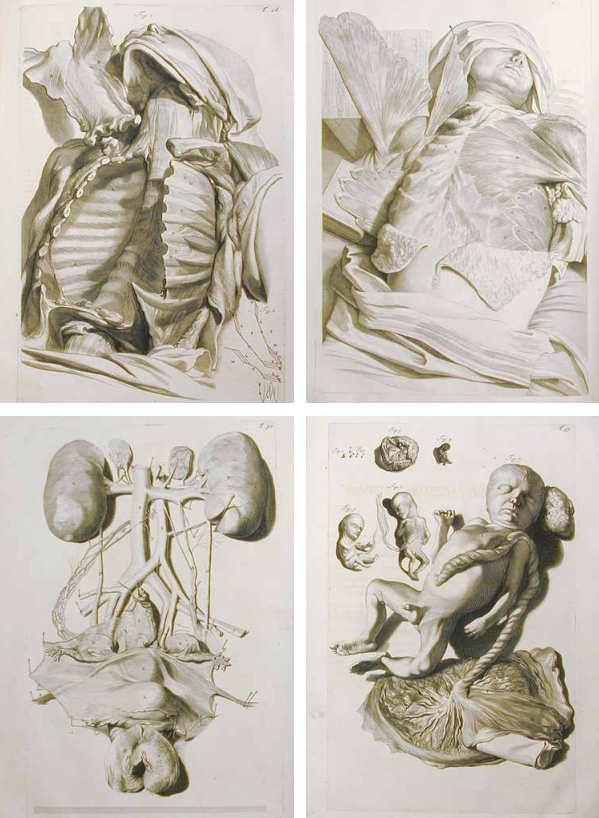

© Military Medical Museum

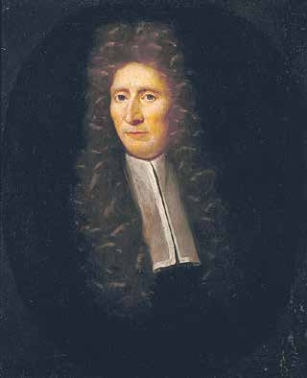

In Amsterdam during 1697-1698 Peter visited the anatomical theatre and attended lectures by Fredrik Ruysch (Fig. 8) and even participated himself, carrying out anatomical dissections. Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731), was a Leiden graduate who became professor of anatomy to the guild of surgeons of Amsterdam and chief instructor of midwifes. He had accumulated a unique and famous collection of anatomical preparations. He had derived a technique for preserving specimens based on what he had learned when working with Jan Swammerdam, another Leiden medical graduate who made important contributions to the study of anatomy. Swammerdam injected blood vessels with coloured liquid wax to investigate the circulation and Ruysch introduced the use of the microscope developed by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek to enable him to inject the wax into the very smallest blood vessels. Ruysch also taught Peter how to diagnose patients, prescribe medicines and carry out surgery. At Ruysch’s home he admired his large collection of anatomical specimens.

Portrait of Fredrik Ruysch,

Oil on canvas,

1694

In public domain

In 1716-1717 Peter the Great visited Fredrik Ruysch again in Amsterdam, but this time he was more interested in purchasing Ruysch’s anatomical collection. The sale was finally agreed for the sum of 30.000 Guilders, an enormous amount in the eighteenth century. This collection was placed in the first Russian museum of the former Academy of Science (now known as Kunstkamera, Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography) in Saint Petersburg. On Peter’s orders, starting in February 1718 the Kunstkamera was extended to contain all examples of birth deformations of both humans and animals in Russia.

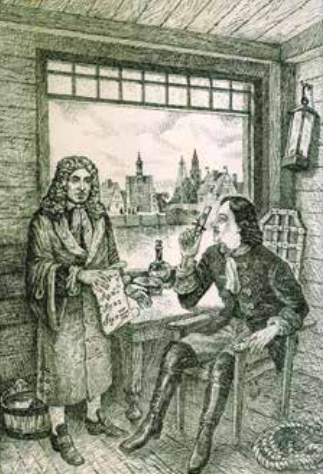

and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

in the City of Delft

2004

From the collection of the Military Medical

Museum of the Ministry of Defence

of the Russian Federation

During his first Great Embassy Tsar Peter also visited the city Delft. On his visit to Antoni van Leeuwenhoek he was fascinated by how the microscope of Van Leeuwenhoek allowed him to “to see such tiny objects” and he took one of the microscopes back with him to Russia.(Fig. 9) After Peter’s first Grand Embassy to Europe, he gave a series of lectures in Moscow in 1699 for the boyars (noble men) on anatomy, with demonstrations on cadavers.

engraved by Willem Swanenburgh

on copperplate

Leiden Summer Theatrum Anatomicum

In public domain

What the Tsar learned and observed during his European Tour had a significant influence on the development of modern medicine in Russia He was well aware of the need for training of medical personnel for the Russian army and navy. Peter had two solutions for this problem: send Russians abroad for higher education and establish medical schools in Russia. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century there were close relation between Russia and Holland in the medical field and many Dutch physicians came to practice and help advance medical education in Russia. The first two Russians sent abroad to study medicine on a scholarship were Pyotr Vasilievich Posnikov (1676 – 1716), and Johann (Ivan) Deodatus Blumentrost (1692-1756). Posnikov was the first to benefit from Peter’s decision to be educated abroad at the states expense. In 1692 he went to the University of Padua, where he was awarded the degree of Doctor of Medicine and Philosophy. He further developed his medical expertise among other cities Leiden, where he attended the clinics of Herman Boerhaave and studied with Fredrick Ruysch. Although he became the first Russian doctor he never practiced medicine. Instead, he spent much of his time as an interpreter and translator for the Tsar. The second Russian one was Johann Deodatus Blumentrost (1692-1756), the third son of the old court physician Laurentius Alferov Blumentrost. He completed his medical studies in Leiden in 1713 and beame Arkhiyater of the Aptekarskaya Kantselyariya (1719-1731), the supreme body for the management of medical affairs in Russia.

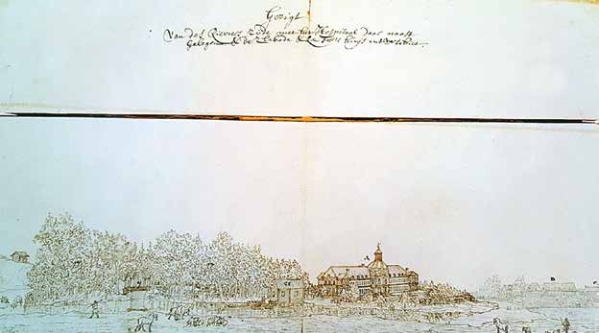

the adjacent hospital

Drawing by Nicolaas Bidloo,

Moscow, beginning of the 18th century

In the public domain

The establishment of a hospital with a school and an anatomical theatre

Sending young Russians abroad to train as doctors did not solve the shortage of native Russian doctors. Until the time of Peter the Great there was no classical scientific medical school in Russia, only a school training barber-surgeons for the army and navy opened in 1654 by the Aptekarskiy Prikaz. The development of medical education along European lines relied heavily on foreign physicians, in particular those from the Netherlands. At the beginning of the eighteenth century the Dutch University of Leiden was at the forefront in the development and implementation of the clinical method in Europe, mainly due to one man, Hermann Boerhaave (1668-1738) (Fig. 10), who was a convinced follower of Hippocrates and Thomas Sydenham, who believed that diseases should be studied and observed in a systematic and accurate manner. Boerhaave was appointed as a lecturer in 1701 to cover for Govert Bidloo, professor of anatomy, medicine and practical medicine, during his absence as personal physician to King-stadtholder William III. In 1709 Boerhaave was appointed as professor of medicine and botany and in 1718 also professor of chemistry. Boerhaave emphasised the importance of visiting the patient at the bedside, combining a careful physical examination of the patient with a physiological and anatomically rational diagnosis, methods introduced earlier in Leiden by Johannes van Heurnius (1543-1601) and Franciscus de le Boe Sylvius (1614-1672). His lectures attracted Russians who played a prominent role in Russian healthcare among them was Tsar Peter the Great. On 17 March 1717 Peter the Great visited a second time for two days, now by yacht, Leiden and its university. The city welcomed him with cannon firing. At that time Rector Magnificus, Herman Boerhaave, and the collective of professors received him. Peter wrote down the establishment of the university, the curriculum, and everything of use in his notebook. He examined the library and all kinds of mathematical and mechanical machines and tools. When leaving the University, Peter was told about its history and its didactic presentations. After that, Peter examined all the factories and manufactories in Leiden and talked into the most details with the masters.

Doctor’s Visit

Holland. Ca. 1660

Oil on wood. 62,5 × 51 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Entered the Hermitage in 1772. Acquired from the collection of

Baron L.A. Crozat de Thiers in Paris

Inv. № ГЭ-879

PHOTO: © THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM, ST PETERSBURG, 2019

Tsar Peter met with Herman Boerhaave, but it was tsarina Anna Joannovna (1730-1740), who invited him to become Arkhiyater. In a letter to his former student Laurentius Blumentrost dated from 1730, Boerhaave officially thanked for the invitation but refused the position.

The Portuguese António Nunes Ribeiro Sanchez, personal physician of Tsarina Anna Ivanovna (1730-1740) and a graduate of the Leiden university and pupil of Herman Boerhaave, recommended Herman Kaau-Boerhaave the nephew of Herman Boerhaave as court physician of the Tsarina. Herman Kaau accepted the invitation and travelled to St. Petersburg with his family at the end of 1741. He was one of the four general directors of the Meditsinskaya Kantselyaria. His parents were, Margriet Boerhaave, sister of Herman Boerhaave and doctor Jacob Kaau. Herman became the heir of his uncle Herman Boerhaave, who had only a daughter, so he attached the family name Boerhaave to his surname.

A Visit to the Doctor

Holland. Ca. 1665

Oil on wood. 60 × 48 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Entered the Hermitage in 1772. Acquired from the collection of Duke ÉtienneFrançois de Choiseul in Paris

Inv. № ГЭ-889

PHOTO: K. SINYAVSKY © THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM, ST PETERSBURG, 2019

In 1744 Herman Kaau-Boerhaave was appointed to the state council and on 7 December 1748 appointed by Tsarina Elizabeth the Great (1741-1761) as a member of the Privy Council, as first personal physician and General Director of the Meditsinskaya Kantselyariya. He died in Moscow on 7 October 1753 and on the express order of the Tsarina his body was interred in a vaulted crypt in the Old Dutch Church. His remains were moved to the Moscow cemetery on May 20, 1815 when the Old church was moved.

Herman Kaau-Boerhaave, like his uncle, had no male heirs and his younger brother Abraham Kaau became his only heir. In 1740 with the permission of the daughter of Herman Boerhaave, countess De Thoms-Boerhaave, Abraham also changed his surname to Kaau-Boerhaave. Both brothers had studied medicine in Leiden under their uncle Herman Boerhaave and both made successful careers in Russia.

Pavel Zakharievich Condoidi (1710-1760) of Greek roots travelled from Russia to Leiden to study medicine, where he graduated as a doctor in 1733. On his return to Russia he initially worked as a military doctor, then as a general staff physician. As an honorary member of the Imperial Academy of Science he succeeded Herman Kaau-Boerhaave in 1753 as General Director of the Meditsinskaya Kantselyariya, a post he held until his death in 1760. During his tenure he introduced a seven-year’s period of study, a new examination system and introduced in the curriculum of the medical schools teaching of physiology, obstetrics, women’s and children’s diseases. Another of his achievements was the establishment of the first Russian Library of Medicine in 1756.

Peter the Great also paid special attention to the armed services, building hospitals for the army and navy in Moscow and Sint Petersburg. In 1715 in Saint Petersburg he established the Second Landforce Hospital and the Navy Hospital on the banks of the Neva along the lines of the medical hospital school in Moscow. In 1716 the Tsar himself wrote military regulations in Russian and Dutch stipulating the number of doctors, surgeons and pharmacists required for the army.

In an effort to increase the number of medical students Tsarina Elizabeth the Great (1741-1761) in 1748 instructed the church schools in Moscow to send more pupils to the medical hospital school. The first ethnic Russian to be appointed the chief doctor of the hospital was the Muscovite Martin Ivanovich Shein (1712-1762), who taught surgery at the hospital school. He was a graduate of the Moscow medical hospital school. Another ethnic Russian, Konstantin Shchepin (1728-1770), also a graduate who had completed his postgraduate studies in Leiden, became the first Russian director of the medical hospital school in Moscow in 1762.

Doctor’s Visit

Holland

Oil on canvas. 21.4 х 25.4 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Entered the Hermitage in 1980. Donation of V.D. Golovchiner

Inv. № ГЭ-10390

PHOTO: K. SINYAVSKY © THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM, ST PETERSBURG, 2019

Development of science in Imperial Russia

Academy of Science

University education in Russia dates from 1724, when Peter the Great established the Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg along the lines of the French Academy, which he had visited in 1717. His idea was for the Academy to function both as a scientific and an educational institute. He donated his library and the Kunstkamera to the Academy. Unfortunately, Peter failed to see his creation as he died on February 1725, before it opened in 1726. After his death his widow, Catherine the First (1725-1727), continued the work of her husband. The first meeting of the Academy took place on 27 December 27, 1725 in the presence of the Tsarina and its grand opening was held on August 1, 1726. The Academy established a grammar school and a university with three faculties (medicine, philosophy and law). In 1726 the grammar school was opened and received 120 students in the first year; and in the second year 58. The university contained a library, curiosities, an astronomical observatory, an anatomical theatre and a botanical garden.

The court-physician of Tsar Peter, Laurentius Lavrentovich Blumentrost (1692-1755), the youngest son of Blumentrost senior, and like his brothers also a graduate of Leiden university, became the first president of the Academy of Sciences. In the years 1726 and 1727 several experienced doctors came to Russia and were admitted to the Academy. These included the president’s older brother Johannes Deodatus Blumentrost, general director of the Meditsinskaya Kantselyariya, and Michael Burger, both alumni of Leiden University. The youngest of the two brothers Kaau-Boerhaave, Abraham, also became a member of the Imperial Academy of Science of St. Petersburg in 1744, when he was still a practicing physician in the Hague. He came to St. Petersburg in 1746 where he first got a position at the Admiralty hospital. In 1748 Abraham succeeded Josias Weitbrecht, who had died in February 1747 as professor of Anatomy and Physiology and left eight scientific manuscripts in Latin. He died in 1758 in Russia and the family name Boerhaave died with him.

Someone worth mentioning is Alexius Protassiev, who first studied medicine in Leiden and afterwards anatomy at the Imperial Academy of Science, where his teacher and mentor was Abraham Kaau-Boerhaave. Protassiev was one of the first native Russians to specialise in this subject and he was appointed Professor of Anatomy at the Academy.

Other Dutch members of the Imperial Academy of Science were father and son de Gorter. Father Johannes de Gorter studied medicine in Leiden and discussed various physiological and pathological theories under the chairmanship of Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (1697-1770), professor of anatomy and rector of the Leiden university. In 1725 Johannes de Gorter became city physician and professor of medicine at the university of Harderwijk. His son David a student of Leiden but graduated from Harderwijk where he became professor of medicine and botany at Harderwijk. Both accepted the positions of second and third court physician to Tsarina Elizabeth and were also elected member of the Academy of Science. After the death of his Johannes returned in 1758 to the Netherlands, already an old man. He left 23 scientific manuscripts in Russia. Another member of the Academy was the German Carl Friedrich Kruse who had also studied medicine in Leiden. He had for a long time served as the chief physician of the Imperial Lifeguards in St. Petersburg. During the reign of Catherine the Great he was appointed in 1770 as assistant personal physician and State Councillor by the court. His wife was the daughter of Herman Kaau-Boerhaave and heir to the Boerhaave heritage. Other famous Dutch professors from Leiden were invited during the eighteenth century to Russia and not always accepted the offered position among others Bernard Siegfried Albinus and Hieronymus Davides Gaubius.

The establishment of the first university for a further development of science

On January 24, 1755 Tsarina Elizabeth the Great (1741-1762) gave orders for the establishment of Moscow University headed by a board of Governors, that consisted of two curators Ivan I. Shuvalov of the Security Council and Laurentius Laurentevich Blumentrost president of the Academy of Sciences, and the general director (later renamed to Rector Magnificus) Aleksei M. Argamasov a member of the city council.

She (1741-1762) issued in 1756 a law that only doctors who had been examined and officially registered by the Meditsinskaya Kantselyariya were allowed to practice medicine. It was expressly forbidden to provide any oral drugs without the signature of a qualified doctor. The practice of medicine was now forbidden to non-qualified doctors (folk healers). The Meditsinskaya Kantselyariya distinguished between scientifically trained foreign doctors (Doctor Medicinae) and empirically trained doctors. The first group were doctors who after their basic medical training had completed postgraduate studies and research culminating in the defence of a scientific thesis. The second group were referred to as barber/surgeons лекарь (lekar), and this distinction was also reflected in the level of salary. During the reign of Tsarina Catherine the Great (1763-1796) the medical improvements in Russia made by her predecessor began to flourish. The number of physicians of Russian origin steadily increased. At the end of the nineteenth century two centres of medical education existed: the Medico-Surgical Academy (now the Military Medical Academy named SM Kirov) in St. Petersburg and the Medical Faculty of the Moscow University named Lomonosov. Also the Imperial Academy of Science played a significant role in the development of Medicine.

Inge F. Hendriks, MA,

Ph-researcher

Department of the Executive Board,

Leiden University Medical Centre,

Albinusdreef 1,

2333 ZA Leiden,

The Netherlands,

Mob.NL.: +31 651364952

Mob.RF.: +7 921 9562730

E-mail: ingefhendriks@gmail.com

Legend to the figures

Fig. 1

The building of the Aptekarskiy Prikaz in the Moscow Kremlin, pen and ink drawing, artist Margarita V. Apraksina, Saint Petersburg, 2016. The author is owner of the drawing.

Fig. 2

Peter the Great, oil on canvas, artist Jean-Marc Nattier, after 1717. In public domain.

Fig. 3

Peter I provides medical care in Azov 1696, watercolor, artist V.I. Peredery, 1950, Image OF-35880. Military Medical Museum of Defence Ministry of Russian Federation, Saint Petersburg. Reproduced with their permission.

Fig. 4

Academy building Leiden University. In public domain.

Fig. 5

Theatrum Anatomicum Leiden Winter, drawing, artist Andreis Stock, 1616. In public domain.

Theatrum Anatomicum Leiden Summer, drawing by Johannes Woudanus, engraved by Willem Swanenburgh on copperplate, Image ID: DFJF35. In public domain.

Fig. 6

Nicolaas Bidloo standing at the table with a book, watercolor, artists of Lenfront Masterskie VSULF, December 1943, Image OF 7787. Military Medical Museum of Defense Ministry of Russian Federation, Saint Petersburg. Reproduced with their permission.

Fig. 7

A view of Nicolaas Bidloo’s garden and the adjacent hospital, drawing by Nicolaas Bidloo, Moscow, beginning of the 18th century. In public domain.

Fig. 8

Portrait of Fredrik Ruysch, oil on canvas, artist Juriaen Pool, 1694. In public domain.

Fig. 9

Peter I and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek in the city Delft, pen-and-ink drawing, artist V.S. Bedin, 2004, Image OF-87224. Military Medical Museum of Defence Ministry of Russian Federation, Saint Petersburg. Reproduced with their permission.

Fig. 10 Portrait of Herman Boerhaave, oil on canvas, artist C. Troost, 1735, Inventory number P02634. State Museum Amsterdam/State Museum Boerhaave. In public domain.